I don’t get travelling. It’s a bit like saying, while gasping for air, that I don’t get breathing because, although I don’t travel less frequently than I used to, I tend to cover shorter distances. No more six-week journeys to Siberia or Mongolia for me.

All I know is that I have to travel – only to come back every time. Obviously, these words are not mine, I’m quoting the Marquis from the The Lay of the Love and Death of Cornet Christopher Rilke. Except that I do come back, whereas the Marquis didn’t.

And once you come back, you feel more at home than if you hadn’t gone away. But this doesn’t explain the journey, it just explains its end and I know that there’s something more to travelling and that’s precisely what I don’t get.

I know it’s important not to hurry and that it’s not good to see too many sights either. What seems important to me is to waste a lot of time in aimless rambling, in strange cafés and restaurants, for this is a noble and dignified kind of wastefulness. After all, the point is not to have a rest in a café, as that can be done just as easily on a park bench for free, with a fast-food burger. Sitting around in cafés and wasting money follows no aim and serves no purpose, except perhaps for pretending to belong to the idle classes so caustically described by Veblen, although I don’t understand his vitriol, for it seems to me that this idleness and wastefulness may contain a key element of humanity.

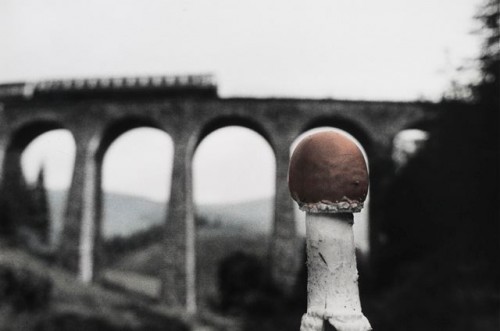

Every real journey involves something splendidly pointless. A real journey has no goal. A journey is the epitome of time-wasting and pointlessness, and my recent visit to the Wilfingen was unnecessary and pointless in just this way.

Wilfingen is a small village in historic Upper Swabia, currently administratively part of the Land of Baden-Württemberg. To me it seems more like a small town, as I didn’t find there anything of a village in the Polish sense of the word. For us, who grew up in Silesia, there’s nothing exotic about this kind of micro-parochiality. Wilfingen is not all that different from my Pilchowice, except for its size, in which respect Pilchowice is bigger, and affluence with all its ramifications, in which respect Wilfingen wins out. In both places you find the castle opposite the church and the houses, half town-like and half village-like; in both places you find little streets radiating out from the square. And when I look at pre-war photos of Pilchowice or listen to my grandparents’ memories, the similarity becomes even greater.

Wilfingen wasn’t my main destination; I stopped there on my way from somewhere else, yet there was something majestically absurd about this journey, for I had to make a nearly 300 kilometre detour in order to get there. Or rather, we had to, for having placed our progeny in temporary care, my wife and I jointly indulged in this absurdity, in what was probably our first such trip in two years.

We approached Wilfingen from the West. Having covered a chunk of Alsace-Lorraine, after crossing the Rhein we entered the Schwarzwald Mountains, which really are dark and covered in forests, foggy and romantic in a very German way. So much so that, were I in the habit of carrying CDs in the car, I would immediately put on some Lieder by Schubert and listened to the piano and women singing in German about the king in Thule, the death and the maiden or a trout; luckily I don’t carry Schubert in the car. Nor did I buy the local speciality, a cuckoo clock.

Then the mountains and forests gave way to hillocks, covered by fields and meadows and tiny, near identical towns with names ending in -ingen, each featuring an inn, everything gemütlich in a truly Austrian fashion. Eventually, following a small road branching off another small road, we found ourselves in Wilfingen, which is identical to all the other little towns in the vicinity.

Naturally, we didn’t end up there by chance. Absurdity is not the same thing as chance. We set out for Wilfingen because I wanted to take a look at the place where Ernst Jünger, a writer whose books mean a lot to me, had spent over fifty years. And so I arrived at Wilfingen. I found the house where Jünger had lived for over half a century and where he died. The house has been turned into a museum for the late writer, but I didn’t visit it as it was closed – and I have no regrets at all, for this injected even more nobility into the absurdity of this trip.

Wandering around like a jolly fool, I was asking myself: so what on earth did you expect to see here? Facing the house is the castle of the Counts Schenk von Stauffenberg. I just peered over the fence and we went on, to the Zum Löwen Inn, where we spent the night. We ordered venison steak, the deer allegedly shot by the Count himself. The owner of the inn, who didn’t understand that for us the journey didn’t need to serve a purpose, phoned the castle to ask if perhaps the Count might be able to open the museum for us and give us a tour, since this was something else he did, apart from shooting deer, and since we had gone out of our way to come… But the Count couldn’t open the museum, he had a doctor’s appointment and so, luckily, I didn’t see the museum. Or the Count.

We washed the venison steaks down with large quantities of the translucent Swabian Schussenrieder and then went to bed feeling full and slightly inebriated. The next morning we went to see Jünger’s grave, but what for? Surely not to invoke his spirit. The dead writer rests beneath a flat, white gravestone, in a small, modest cemetery, together with his two wives and two sons. A linden tree he himself had planted twenty years before he died grows nearby. There are little hills, fields and groves all around. And that’s all there is to Jünger, so why did I make that 300 kilometre detour, pathetic as a teenager making a pilgrimage to the house of her idol hoping to see at least his shadow in the window? After all, I didn’t want to learn anything, to understand anything, I wasn’t after food for the imagination, nor was I interested in the museum. I could have had venison steak in lots of other inns, and there are plenty of places in Germany where one can have good beer. So what was the point of it all?

None at all. And it was wonderful.